Clotilde: Marwa, first of all, I would like to thank you for making time to attend to my questions. I am fascinated by your work and take on Syrian architecture and its social counterpart – you have extensively written about the social impact of architecture and its role in expressing social identity in Syria.

I would like to talk about mass housing; this is an issue that is affecting most cities all over the world. Even though the international forum is rife with discussions, not much advancement has taken place.

What do you think are the issues that surround mass housing?

Marwa: That it exists! Mass housing as its name indicates is a herd encapsulating approach, where people are meant to be boxed away from sight. There no sense of neighborliness can grow, nor businesses can thrive, no architecture, nor streets, merely box blocks where no one by choice would live.

Clotilde: When talking about mass housing, it is easy to associate that to large developments that follow an industrial, “cookie-cutter” approach and more than often sustainability issues are not taken into consideration, a sort of function distant from the form. However, your submission into the 2014 UN-Habitat, Tree Unit, won the Syria category and changes the game of mass housing.

Could you tell me more on how the design was developed and what cultural motifs you drew on for the development of the design?

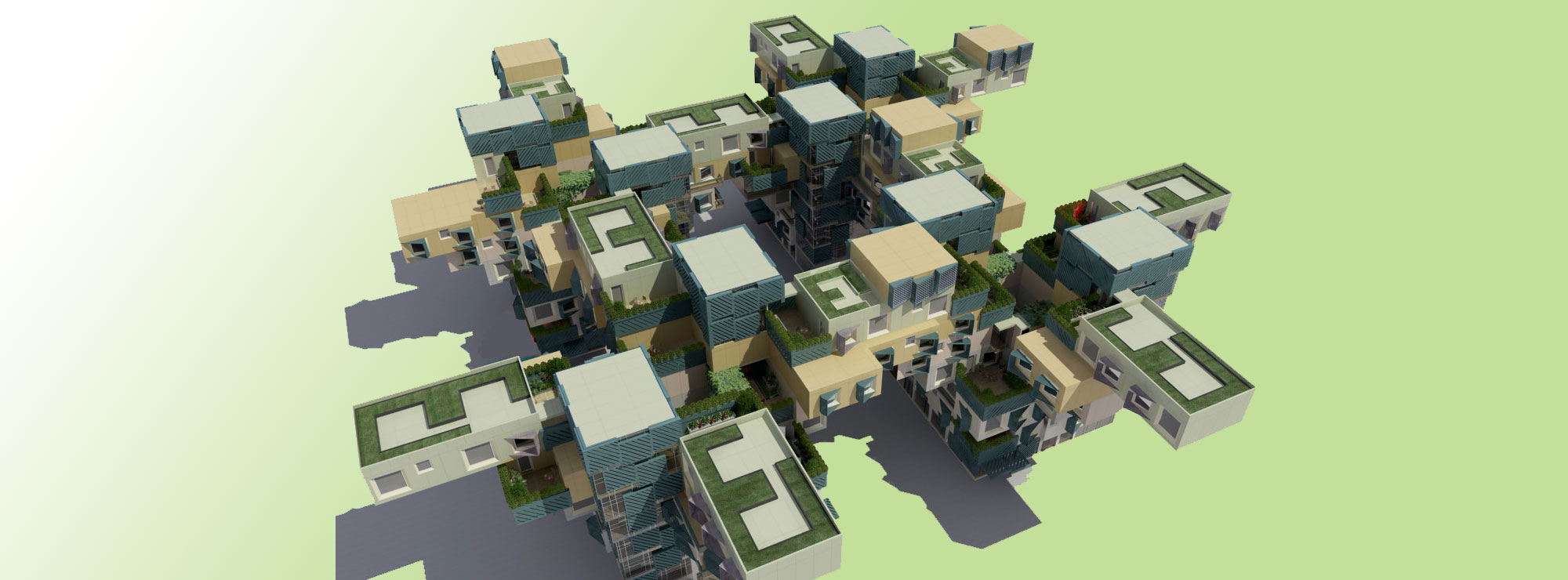

Marwa: The Tree Unit is a unit made up of a cluster of courtyard houses, where privacy and nature are the main focus. All courtyards should be while open; protected from being viewed by others, including the neighboring windows.

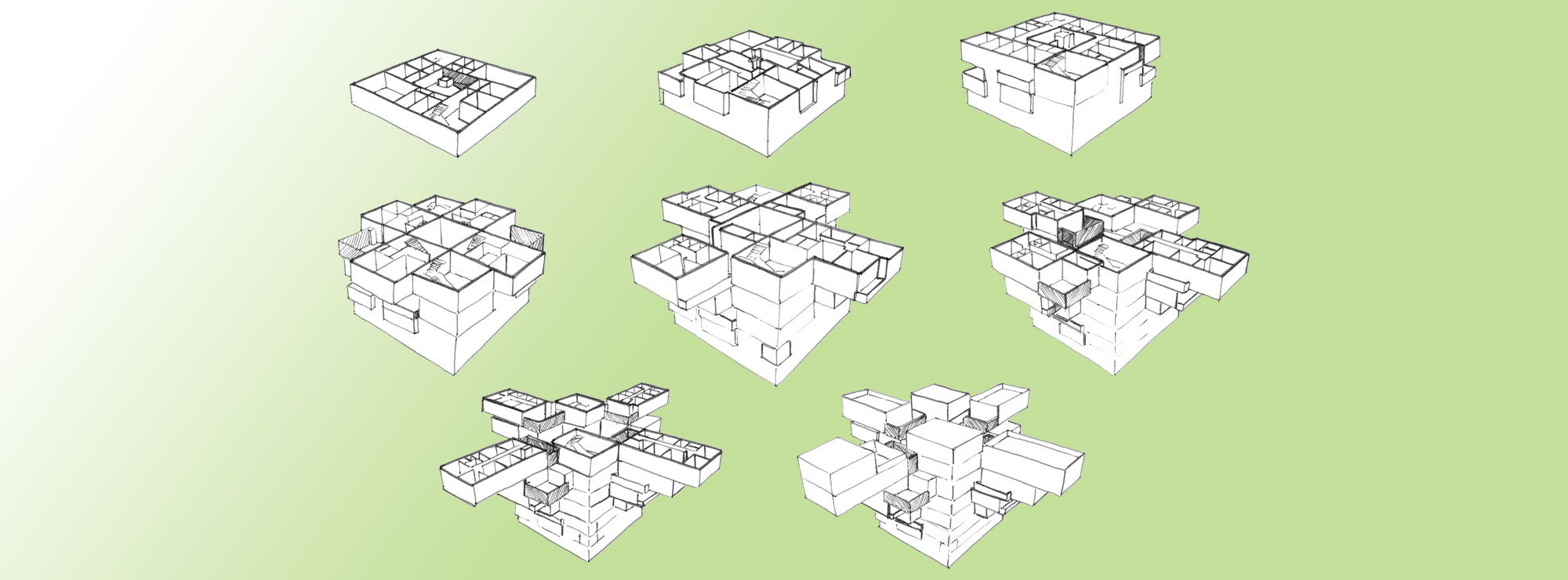

The task was to reach this goal while maintaining the traditional setup of the apartments and to create an urban unit that can unfold in four directions and connect with the mirrored units around. Namely; to extend the architectural cluster (the tree unit) into an urban cluster through connecting to the unfolded surrounding units.

In this way, the quality of growth was established, so it is not a literal reference to ‘tree’ as one may imagine at first, rather the quality of what trees do; i.e. growing. It can grow horizontally (in the urban sense) and grow vertically (in the architectural sense).

That’s how you can spot the conceptual difference between this design and the design of Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 in Montreal. Some people made the connection by comparing two shots from the two projects. I have to admit that at first sight, they may appear very similar, but I see no real connection specifically because the two spring from totally different concepts and understanding and more essentially they reach different outcomes in creation, adaptation and design logic and organization. My design is built on a unit able to grow not randomly or accumulatively, rather intertwined geometrically and rooted in traditional culture.

The real resemblance I tried to make was to the street bridge which can be found in the old Islamic cities in Syria (I’ve always been fascinated by this structure and what impact it can make on the street view, shade and light, and weather protection. As well as the design fluidity and flexibility in space making within the apartments; this was applicable in the tree unit when the apartments in neighboring units can exchange room space according to the determined apartment size).

My design used courtyard housing as a cultural, ‘sustainable’, functional, and social form.

Clotilde: What is the role of sustainable solutions for the built environment in that design?

Marwa: My design was based on a comprehensive study I did for the locality’s social make-up, economic activity, lifestyle forms, property status and sizes, main infrastructure network and surrounding amenities, and so on. But I will explain in the following question, I didn’t look at sustainability as an isolated layer. My design used courtyard housing as a cultural, ‘sustainable’, functional, and social form. The same goes onto the street bridge; and wind tower (inside the unit), etc. These solutions were imbedded in the design thinking as were other ‘pieces’ of the design, the aim was that none of which targets one goal or achieves merely one end, all the details work in the service of the whole as well does the whole in confirmation to Leon’s Battista Alberti famous quote on beauty.

Clotilde: When Bjarke Ingels talks about hedonistic sustainability, he mentions that there are misconceptions on the matter and sustainability is perceived as a moral sacrifice. However, even though the sustainable design has been extensively linked to improvements in quality of life, it is now seemingly predominant mostly in high-end designs. What, in your view, hinders a sustainable approach from being incorporated into mass housing programs in emerging economies?

Marwa: I think the main issue with sustainability today is that it is being used as marketing brand; namely to sell certain structures and building materials more widely or more expensively than others. While architecture is essentially about targeting several goals which to be integrated as a coherent whole; functionality, efficiency, and what became to call sustainability should be among these goals, not become the complete whole.

In older architectures sustainability used to be regarded as part of function

In older architectures sustainability used to be regarded as part of function; a building would function well if it’s efficient, if it’s durable and pleasant for use in different contexts, among which are different weather circumstances and different site resources and energy consumption. Only because mass housing is not aimed to be part of any marketing process, rather as a final resort for people who cannot afford otherwise, there is no need for the use of ‘sustainability’.

Clotilde: “Architects design ecosystems, so not only the flow of people but also resources” – do you agree with this statement? Do you think this is upheld in the international architectural scene?

Marwa: I completely agree. Jane Jacobs is one of those who addressed very powerfully the economic impact of urban planning. But from that scale addressed by Jacobs, we can note how it also trickles down on the various scales of architecture. While creating certain channels for people we at the same time spreading the shapes of networks that control and in many times dictate the shape of their relationships and flow of recourses created and exchanged as I try to describe in The Battle for Home.

Clotilde: I am writing from Cape Town, which like most African cities reflects different cultural streams with the coexistence of suburbia areas, industrial and informal settlements. Besides the high-end projects, housing developments are not often being designed with a community-driven approach, which looks at the creation of spaces for public participation. Given the separation traits that have characterized many cities in the world, how feasible and doable is it to introduce and promote urban planning that creates generous spaces that fosters community interaction?

Marwa: The Battle for Home has proved to me that we face a common universal problem in all of our cities around the world. But it is, as any serious problem, may sound too complex and challenging while in fact, all it takes, once identified, is the power of good will. I’m convinced that it is a matter of decision, the challenge is how to convince the wealthy and the greedy that it is in their benefit as well to build in a fair and right way, how to let them trade the immediate profit for a longer and more sustained one. I believe the war erupting in my country could make a good case.

Clotilde: Architecture literally surrounds us but its impact is sometimes hindered by personal issues/problems in our daily lives. How do we start conversations at a community level, to appreciate or critically engage with the forms that surround us?

Architects and planners have the responsibility to be engaged in the lives of those who they design and offer solutions for

Marwa: Architects and planners have the responsibility to be engaged in the lives of those who they design and offer solutions for. We often lack this in our profession ever since the early stages of our architectural education. I find comparing architecture to medicine offers a helpful analogy. Architecture as medicine is a serious profession (although many tend to take it much more lightly) which affects the lives it touches very powerfully and deeply to a degree mostly is overlooked, but the war in my country shows that the consequences can be equally as deadly. But unlike medicine our education is not properly based on user as often we are far too immersed in the act of ‘creation’ that we forget all about the user, or alternatively we ‘invent’ for our buildings a ‘special’ kind of users; they could be critics, magazines’ editors, art historians, or public figures looking to be immortalized by our designs. Hence my view is that the conversation should not start at a community level, rather on an educational and professional level that could end up (if needed) at a community level.

Clotilde: What and who inspire you?

Marwa: When honest and genuine everything and everyone inspires me. In our Islamic culture we have a prayer that asks to be ‘of those who listen to the saying and follow the best of it’; I found this approach most rewarding as it presents in its holistic concept everything as a source of knowledge but also as a subject for scrutiny, nothing is excluded but nothing also is taken for granted. An act of constant refinement.

Clotilde: Thank you very much for your time.

Follow @marwa_alsabouni

Marwa Al-Sabouni’s Ted Talk

Mawwa Al-Sabouni on ArchDaily

The Conversation Podcast on BBC